Why I Study the Russian Revolution

A not-so-short self-indulgent article about my obsession with this period of history (and workers democracy).

Anyone who knows me knows I am obsessed with the Russian Revolution, I could talk about it for hours! My interest has been mostly confined to this very specific period from the 1917 February Revolution through to the death of Lenin in 1924 – don’t ask me about Stalinisation, the purge or De-Stalnisation (watch The Death of Stalin (2017) instead). I have invested an absolutely stupid amount of time and money into reading about this fascinating bit of Russian and Soviet history. Every October since 2017, I think about writing about my accumulated reflections on it again and again every year, but this year I finally get down to it.

The (small s) soviets: Russian Councils and Direct Democracy

My entryway into socialism was not the more typical route through the economic writings of Marx and Engels, I first heard about Leon Trotsky as the leader of the first soviet (the Russian word for council) in the 1905 Revolution. From just reading the Wikipedia page, I stumbled onto what seemed like the perfect form of politics at the time. These workers’ councils were directly democratic and extensively deliberative in nature – the perfect antidote to the corrupt money politics of Malaysia and democracies captured by corporate power in the West. These soviets were more than unions, they provided education, healthcare, security and much more to members of the Russian working classes and peasantry.

Through my further reading into the subject and understanding of the February and October Revolutions of 1917, I would discover that it would be the Bolsheviks – the very people who championed the soviets, including Trotsky himself – were the ones to destroy these democratic councils. More than that, they would defeat a largely forgotten internal faction of Bolsheviks – the Workers Opposition who fought for a greater workers’ democracy of the Civil War years (1918-1921). Most accounts of the soviets movement end with the Bolshevik forces putting down a rebellion at a naval base in Kronstadt led by radical sailors who demanded the return of radical soviet democracy in 1921. All this happened while Lenin was still at the head of the party and the entire state, the very same person who preached “All Power to the Soviets” all the way to the victory of the October Revolution.

Me delivering my workshop at Rumah Attap in Zhongshan Building.

Right after my research and workshop on the soviets in October 2017 – in conjunction with the 100th anniversary of the October Revolution, I found myself leaning towards the council communism of Rosa Luxemburg and the anarcho-syndicalism of Rudolf Rocker, feeling pretty sure that these more democratic forms of socialism would have been a much better substitute for the anti-democratic and bureaucratised Soviet system of political power. I thought very little of Bolshevik leaders like Lenin and Trotsky at the time – no need to mention Stalin who seemed like an utter monster once you look into the details.

Contradiction of Power: The Bolsheviks Ruling in the Name of But Against the Proletariat

As I continued to explore and dive deeper into these historical events, I quickly realised that focusing solely on the soviets as institutions without considering the external environment was childish. To do so would be to ignore the reality of how our social world works, in a way that Marx once put it, “Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past.”

And as such, the Bolsheviks could not have picked a worse country or empire under worse circumstances to have a revolution succeed. A primarily agricultural economy with a small proletariat, surrounded by former imperial enemies and powerful capitalist nations – eager to crush an ideology that threatened their fragile national politics. When one looks at the details, it is almost miraculous that the Red Army defeated the Whites and recovered much of its territory. Their revolution survived the initial assault.

The price of survival, however, was heavy. There was no time to meticulously and patiently persuade the peasantry and other parties and workers that the revolution needed to be defended with their sacrifice. In order to organise an army and fight a civil war, democracy has to be put on pause and power centralised in the Communist Party. This centralisation of power even wiped out the democracy within the Party, indirectly paving the way for Stalin and his more bureaucratic and anti-democratic ways. The further tragedy was that because this was the first successful socialist revolution in the world, many other liberation movements would mimic the vanguard party model set out by the Soviet Union and inherit all of the flaws of this system of politics.

And yet, when one considers more deeply all their circumstance and the choices they were confronted with, one senses that they were prisoners of their time and place. They did not choose to fight a civil war with the Whites. There were few options but to requisition grain from the peasantry – often against their will – in order to feed the Red Army. As much as they tried and hoped, socialist revolutions never overtook Germany and other Western powers, no future socialist states came along to help them develop industry. If the choice was to try to win and defend a revolution in difficult circumstances or to flee, be killed or surrender to fascist forces, who would choose the latter?

Considering the Achievements of the Russian Revolution and the Soviet Union

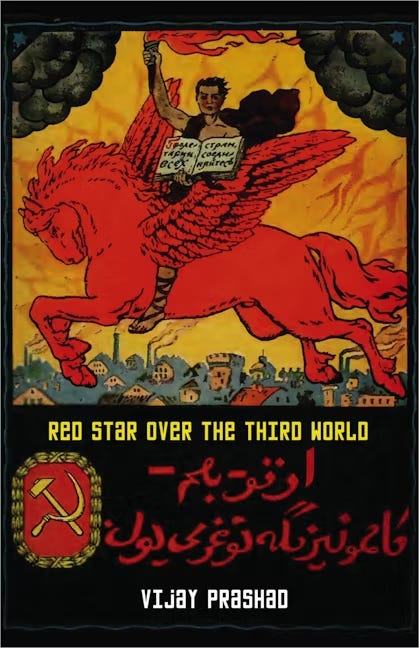

In parallel with arriving at this more grounded position on the Bolshevik’s choices and the conditions they found themselves in, I was also being confronted with the world they had created, primarily through the writings and online lectures of Vijay Prashad. His book, Red Star Over the Third World – published in 2017 along with EVERYONE ELSE for the centenary – is a short but concise book that looks at the positive impact of the October Revolution on the colonised world. The Revolution was the first ripple of national liberation and socialist transformation that would spread throughout the world. The emerging colonised nations at the time could not even think of democracy as they were dealing with poverty and imperial domination. The Soviet Union held the promise of developing the productive capacities of their societies so that people did not carry on under the misery of capitalism and colonialism.

While the Soviet Union did provide some really shit direction to some parties and communist governments – holding back some socialist revolutions in order not to anger the West in some cases, it was able to and did provide material support to revolutions that changed the dire political reality of the post-colonial states. Whatever you think about their flaws and the constraints they would impose, in the final analysis, I think the world is far worse off for not having the Soviet Union and Comintern (the Third International or Communist International) as a major supplier of materials, funds and ideological training for communist and socialist projects around the world.

One indirect effect the Soviet experiment had on the world was that it forced social democratic and even conservative governments to retain and enhance their welfare states and democratic freedoms. This was done for cynical reasons of wanting to make the capitalist First World appear more free and fair – when nothing of the sort was true for the vast swathes of its peoples. But this nonetheless opened up some space for ordinary socialists of the non-communist variety to to challenge and sometimes take power in bourgeois democracies. Now, without the Soviet threat, the neoliberalism of the centre (left and right) and fascism of the far right are the only two choices offered in many societies.

Reflections After EVEN MORE Reading about the Russian Revolution

After delivering my 3-hour workshop on the soviets (I know, it should’ve been 30 minutes for everyone’s sanity) on 21st October, I spoke on a panel with representatives from Parti Sosialis Malaysia and Sosialis Alternatif on the Revolution a week later. At the time, the lesson I took away from my intense reading of the 1917 Revolutions was to prepare the day after the revolution. I thought that if the Bolsheviks just had the precise plans and right ideas about socialist democracy and its implementation, they would not have had to do such brutal things to stay in power. My presentation of the soviets (again the councils, not the Soviet Union) was my small but naive attempt to morally rescue the Soviet project against the mistakes of the Bolsheviks.

After many years of reading more, considering and reconsidering what happened in 1917 up till Lenin’s death, I landed on a sort of ambivalence. I no longer feel the need to disavow Soviet communism as somehow distinctly evil in comparison to council communism, anarchism or other types of socialism. I more strongly believe that it is meaningless to think in terms of good and bad guys, leaving my speculation of intentions as a matter of psychoanalysis and material conditions rather than of virtues. I can recoil at the cruelty of the Soviet state without needing to condemn the entire socialist experiment along with all its achievements.

But all this is probably not why I wrote this already needlessly long article. In the end, despite all the tragedy and brutality of this period, I still find myself drawn to study this period* because I cannot look away from its irresistible atmosphere of possibility. I read dry academic books about this period because I am still inspired by the attempt of the soviets and the Bolsheviks to make a better world. I imagine what it would have been like to have those democratic councils survive, thrive and challenge the dominant global order of bourgeois democracy. I enjoy and am still excited to read and write about this moment in history because it reminds me of a world that was and ultimately, how it could still be.

“The past is a resource not a destination – it reminds us of what is possible.” - Vijay Prashad, Red Star Over the Third World

*Sidebar: In 2018-9, I wanted to do a master's on it comparing it to my second favourite historical period the Spanish Revolution / Civil War from 1936-9, even wrote a whole proposal for it on industrial democracy.